When I started my professional career I was not doing software engineering, but rather reverse-engineering. Taking a compiled binary, disassembling it, and trying to understand what it does. My job was essentially reading code, with the stated goal in my job description was “vulnerability research”. Since then, I moved to the other side, and am now doing “forward engineering”.

While it is very tempting to say that as programmers (or developers, or software engineers, or whichever term you’re comfortable with) we only write code, we know that this is not true. If fact, we spend a lot of our time reading code. Be it code reviews, reading docs, debugging, or finding that one line of code we need to stick in someone else’s face and say “See!?!?!?! I told you!!!”.

Reading code is a vital part of any code-related role. Be it forward- or reverse-engineering. That said, the perspective if very different. I see that difference when talking to my friends about code, some of them being developers and other reverse-engineers. But I also see it in how I approach my tasks. My approach to reading code is dramatically different between development and reverse-engineering tasks.

Part of it is the difference in goals - as a software developer, I want the code to work well. I am not (usually) looking for bugs, because I really don’t wanna find them. As a reverse-engineer bugs are what we’re looking for. This leads to a different perspective. In addition to that, as a developer I tend to let my hubris control me, assuming that I can write bug-free code. That I can understand the entire system. When researching code for vulnerabilities, the assumptions are different. First and foremost - all systems have bugs. We just need to find them. And second - systems are big. Too big. This means that we need to focus, get to the interesting parts of an unknown system as fast as possible.

This, in my opinion, also leads to very different tools.

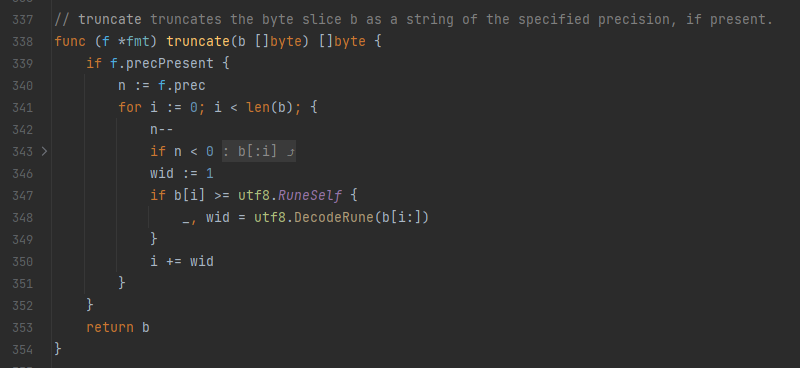

The developer’s tool of choice is a code editor. Be it vi, or emacs, or VSCode, or any other editor. We read the code as text, and process it as text. The editor might give as some colors or linking, but its still text. When we want to know whether 2 functions are similar, we read them both. When we want to know if a function has a complex flow - we read it.

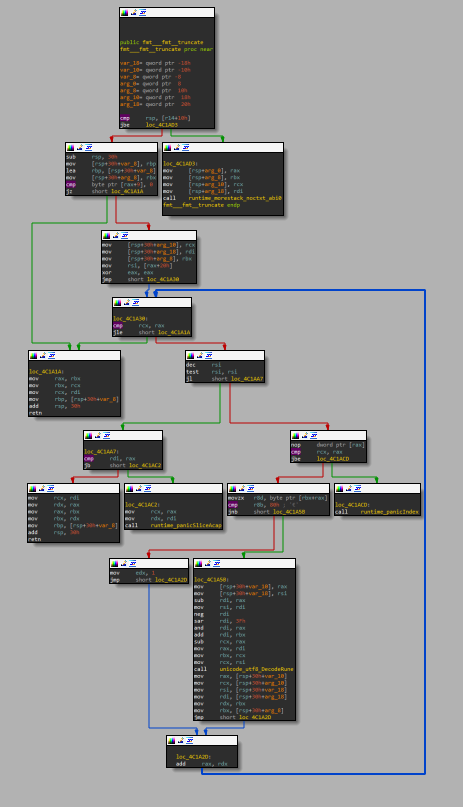

The reverse-engineer’s tool of choice is often IDA (or Binary Ninja or Ghidra or Hopper or something similar). While those tools do allow reading the disassembled code as text, they also offer an additional view - a graph view.

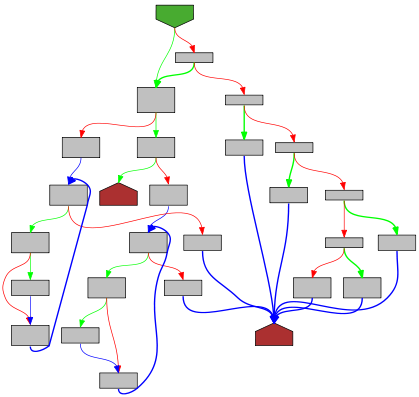

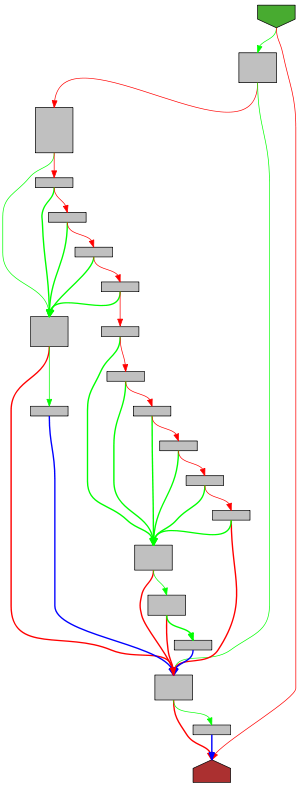

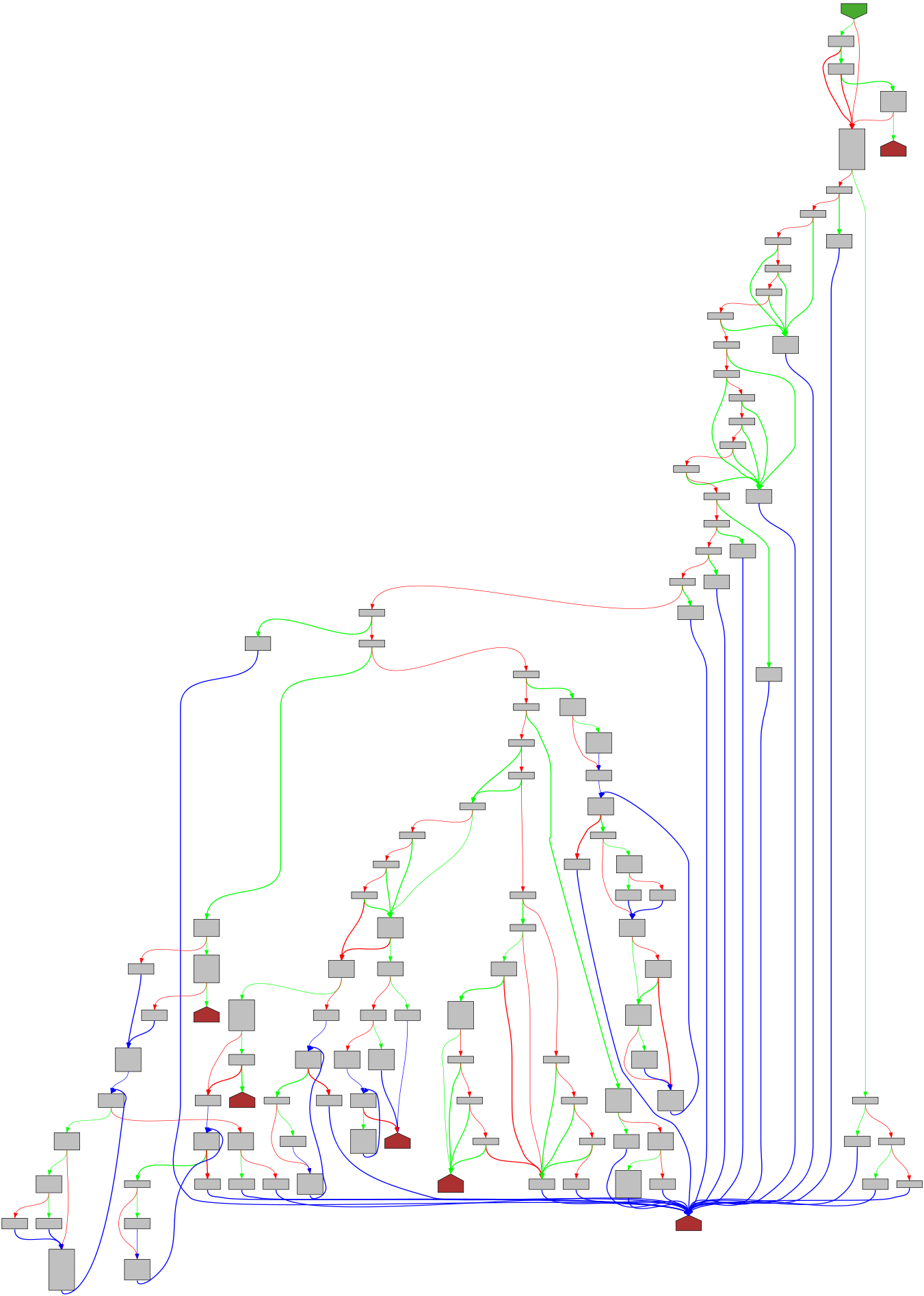

With a bit of training and getting used to it, the Graph view allows a reverse-engineer to quickly discern the flow of the function. With green and red arrows denoting the true and false branches of a condition, blue lines denoting unconditional jumps, and bold lines for backlinks (usually loops).

While the graph does not convey all the information about a function, it still conveys a lot. It makes it easy to see if two functions are similar, or if a function is complicated.

I like this ability, and I miss it dearly in my developer tooling. So I started playing around with graph-visualization of functions in Go, to see how it turns out. Using the least amount of code I could - taking advantage of Go’s SSA1 libraries, and graphing using GraphViz - I managed to create something that, while initial, I’m very happy with. The project is called go-overview-graph and renders source-code and graphs side-by-side. Here are some example graphs, because they are so pretty! I highly recommend going over the website and having a look yourself!