If you go to any of your colleagues now and ask them, “can a function in C++ return itself?” they will probably give you the wrong answer. Now ask them what the return type of the function is going to be. Here, let me help you:

| |

Great! But it doesn’t compile. and neither does

| |

It turns out that C++’s type-system does not allow for recursive types. This is annoying. There is no reason why a function should not be able to return itself. It is even more annoying given that object methods can return the objects that hold them:

| |

This code works. And for obvious reasons. Object methods are not a part of the object. They do not affect the object size or its construction. They are just a syntactic utility. There is no type-system recursion going on here.

With functions there is obvious type-recursion. But if you look at the work the compiler actually has to do - it seems absurd. A function is never constructed, it just is. It is not allocated. The function’s signature changes nothing about the type.

| |

See? No missing information. The compiler has all the knowledge it needs, but the type-system still prevents us from writing our code (or, in this case, from writing it in a type-safe manner). We can do better.

We already know that objects can be used to break type recursion. Let’s see if we can use them here without creating so much boiler-plate code:

| |

The answer is yes. We can. Just substitute this class for the failed type definition of the first example and everything works as advertised. But how does it work?

To break the type-recursion, we create a proxy object. Its sole purpose is to hold a function pointer and call it.

Line (1) defines the function type that we expect to hold. Note that there is no direct recursion there. (2) is the constructor, taking the function pointer and storing it. (3) is where we forward the call to the function pointer. Note that here, too there is no type recursion as the type of the class is distinct from the type of its operator() function.

As a bonus, this compiles identical to the reinterpret_cast<void*> version in both Clang and GCC when using -O3 (see here and here), and at the same time maintaining type-safety. Zero-cost abstraction at work.

But why is that interesting? What are the use-cases?

Well, during the last few months, I’ve routinely consumed one programming-related talk per day. I find it a great way to expand my knowledge, and far easier to do than reading an article every day.

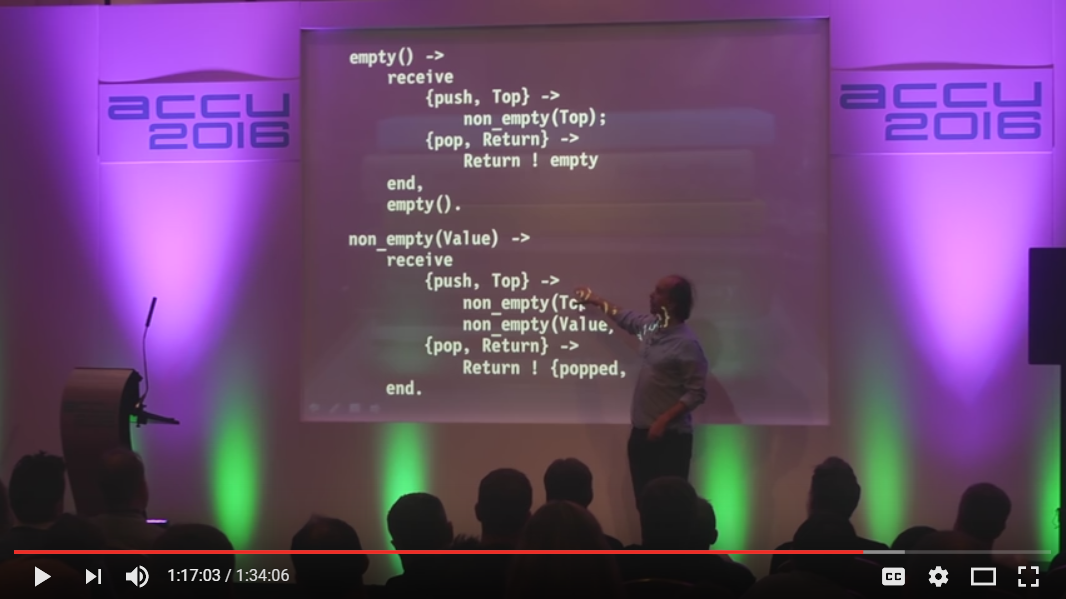

Last week, while working on some minor state-machine, I came across Declarative Thinking, Declarative Practice by Kevlin Henney. Upon seeing this slide:

I thought - bare functions instead of the State design pattern? I have to try that! So I went ahead and wrote my code, iterating through the steps described above.

At a quick glance, the functor solution may seem satisfying. But in effect functors, unlike functions, have different types and cannot be assigned to the same variable. To bridge the gap, we use an abstract base-class and polymorphism. Once we do that, we are forced to use pointers to hold the states. I use std::unique_ptr as I don’t want to manage the memory myself.

| |

The proxy-object trick, however, has no such overhead. We know that we are using objects, but the code does not show it. The compiled version is far simpler as well (see here and here).

| |

Enhancing it a bit, to handle events and operate on a context, we still maintain very simple, straight-forward code. For the purpose of this example, abort() and printf() are used instead of throw std::runtime_error and std::cout because the compiled output is easier to read. See compilation here and execution here.

| |

For those keen on functional programming, we can even pass in a const reference to the context, and return a new context along with the new state. Compilation, execution.

| |

And that’s it. We have a state machine based on pure-, bare-functions, in C++. It has a nice, simple look to it and as we’ve seen, compiles into far simpler code than the alternatives. On the way, we’ve also learned a bit about C++’s type system and how to use objects to overcome its limitations.

In the next post (soon to be populated now online!) I will show some exciting (read: never use in production) dark template magic to both generalize the State object and to get some compile-time guarantees. Stay tuned!