Writeup of my talk about the cpppy library

A few years ago I gave a talk about implementing C++ semantics (namely, destructors) in Python. After giving the talk, I published my speaker notes and slides, to make it as accessible as possible, even to people who don’t wanna watch a video. I was quite pleased with myself, until a few weeks ago when I wanted to look up a detail so that I can reference it in a new blogpost. I went to the speaker notes, started reading, and oh. Oh no. I could get through it, but it really doesn’t hold up on its own despite my memory of it being “everything I said during the talk”. That’s quite unfortunate, as I am very pleased with the work I done for this talk, and want people to happen upon it. Which brings us here - this is that talk, but as a blogpost.

But Why?

When coming to implement C++ semantics in Python, the first question we need to ask ourselves is “why?”. Why would we want to take anything (other than performance) from C++ into Python? After all, C++ is a low-level language, mostly “expert oriented”, and is slowly becoming more “Pythonic”. And on the other hand, Python is a high-level language, it is beginner friendly, and has far fewer footguns than C++.

The answer to that question is resource-management. In C++, all resources are handled the same way. Be it allocated memory; a file; a lock; or your own resource - they are all handled using the same mechanism. In Python, on the other hand, different resources are handled differently. While memory is managed for you by the garbage collector, all other resources must be managed by the programmer.

Before you say anything - no. Python is not C. We don’t have to call the cleanup functions manually. Instead, Python gives us context managers.

Context Managers

Context-managers are relatively straight-forward.

To use them, we use the with statement as follows:

| |

Then, the language uses our FileReader object to wrap the indented block, roughly as follows:

| |

Before entering the indented block, we create our FileReader and call its __enter__ method.

Then, we run the contents of the block.

Then, on leaving the block, we call __exit__.

If an exception was raised from the block, we’ll get the exception info and have a choice to either silence it (by returning a True value) or re-raise it (by returning False).

If no exception was raised - we’ll get get no exception information.

To define a context manager, all we have to do is add an __enter__ method and an __exit__ method to our class:

| |

Real Code

This is well and nice, but let’s look at some real code, a redacted version of something we had running in production:

| |

We had a zip file containing many small files.

So to make reading fast and simple, we read all the files into memory when initializing the reader.

Then, when we needed a specific file - we just accessed it in the data dict.

This way we only unzip once, which was a significant performance gain.

The usage of the class was also very straightforward:

| |

We were fairly pleased.

But, as time went by, we ran into issues. The data files we were reading changed from being tiny (<10MiB) to huge (>5GiB). As a result, we could no longer keep the files unzipped in memory.

The “easy” solution would keep the path, and open the zip file whenever we read a file, unzipping only the desired file. This works, but due to the need to parse zip metadata, it adds a significant overhead in execution time.

The solution we went with was to create the ZipFile object (thus parsing the metadata) and hold it in our ArchiveReader class.

Then, when we read a file, we open and unzip only the said file:

| |

Unfortunately, now that we hold a ZipFile object, we need to manage it.

To do that, we had to make our archive reader a context-manager:

| |

Which, in turn, changes the usage of our reader:

| |

In turn, this demonstrates a bigger issue. Holding a context manager as a member changes the interface of our objects, forcing them to be context managers as well. This change propagates up to all respective owners, and up the stack to the point where the top-level object is created. As this is a breaking change, we must be able to change the code that uses our object. In the general case, this is not possible.

C++ Destructors

C++, however, has a solution to those issues - destructors. Destructors are what makes C++ resource management work, and they have 3 key properties we’re interested in. They are:

- Automatic

- Composable

- Implicit.

Automatic Invocation

The invocation of a destructor is automatic. When we leave a scope, they are called automatically, no matter how we leave the scope.

| |

Seamless Composition

Destructors of member fields are called automatically, making composition easier. If we add a new member, we know that it’s destructor will be called when it is needed.

| |

| |

Implicit Interfaces

Last but not least - destructors are implicit in object interfaces. Objects with user defined destructors and objects without them are all used the same way.

| |

This is even if we don’t define them, they always exist, for all objects. This means that when we write our own destructors, our interfaces don’t change, and no change is propagated.

Our Goal

With that in mind, we want to bring destructors from C++ to Python. Converting our archive reader from this (11 lines of code, 4 are dedicated to resource management):

| |

To this (7 lines of code, 0 dedicated to resource management):

| |

And ensure that our usage remains the same as the original ArchiveReader, with no context-managers and no interface pollution:

| |

Don’t Try This At Work

Seriously, just don’t.

It’s all fun, and standard, and truly painful in a code review or debugging session.

With that in mind, let’s start!

Implementing C++ Destructors in Python

Automatic

Since our target class is a bit complicated, we’ll be joined in our implementation

journey by a simple class called Greeter.

The greeter is a simple class.

It takes a name on construction, and says “Hello”.

On destruction, it says “Goodbye”

This will allow us to keep track of ctors and dtors as we progress through this post.

| |

Hello, 1!

We have a greeter!

Goodbye, 1.

Our first implementation is as straight-forward as can be. With a constructor and a “close” method to act like our dtor.

The next step is pretty straight-forward.

Since Python already provides us with context-manages and the with statement, we’ll use them and see where it gets us.

| |

Hello, 1!

We have a greeter!

Goodbye, 1.

Stacking Dtors

What if we want more than one Greeter? No problem!

Just stack the context-managers!

| |

Hello, 1!

First

Hello, 2!

Second

Goodbye, 2.

Goodbye, 1.

Then again, this type of nesting can get unwieldy quick. We need something better.

Since we’re already stacking context-managers, we can use a proper stack:

| |

The DtorScope will hold all of our Greeter objects in place, then call their __exit__ methods when we leave the with context:

| |

Hello, 1!

Hello, 2!

Goodbye, 2.

Goodbye, 1.

And with that, we’ve rid ourselves of the nesting issue. It works, destruction is automatic, it’s fairly straight-forward, and all too explicit.

Implicit

Now that our destructors get called automatically on scope exit, we want to make sure that we don’t need to write any code to make it happen.

If we could, we’d like our function to look like this:

| |

And have it implicitly do all the plumbing we managed earlier.

First, since we always want to push our objects onto the dtor stack, let’s make it part of their construction.

| |

That’s a good start.

We can no longer forget to push our greeters onto the DtorScope, and we saved a couple of lines.

That said, we’re explicitly repeating and passing around a construct that should be implicit.

To pass the dtor_stack implicitly to the Greeter class, we need to store it somewhere.

In our case, we’ll use a global variable!

And just like function calls go into a stack so that we know where to return, so will our DtorScopes.

So instead of a single global variable, we’ll have to use a global stack.

| |

This is the same as our previous dtor-scope, but now we keep a global stack of scopes. This allows us to always tell which dtor-stack to push our instances into without naming the stack.

| |

Much better, but we still need to explicitly create the scope inside every function.

Decorators

However, since the dtor scoping mechanism has nothing to do with the function itself, we can use it at the callsite instead of inside the function, and it’d work exactly the same.

| |

This will have to be done on every callsite, so we add a utility function to help with that.

The *args, **kwargs syntax is there to pass along any and all function arguments unchanged. Think of it as Python’s version of perfect-forwarding.

| |

Alternatively, we can take the function and return a closure that includes the scoping.

| |

Inside _wrapper we capture f from the parent scope.

As Python is reference-based, we don’t need to specify how to capture.

Next, since Python is dynamic, we can replace the original main function with the scoped one.

| |

Here the wrapper holds the previous version of the function, while the name main is bound to the wrapped version.

In Python, wrapping a function and replacing its original is a common operation. Because of that, we have some syntactic sugar called “decorators”.

| |

This is functionally equivalent to the previous snippet, but is cleaner and more expressive.

And with that, the inside of main looks the way we want it.

Import Hacks

We still have a problem, though.

Even if main looks nice, we had to decorate it with cpp_function.

Having to do that to every function we write for it to work is not very “implicit”, is it?

What if instead, we could just write from cpp import magic, and have that “magic” decorate our functions for us?

| |

Nice, isn’t it? So let’s get to it!

The Magic Function

As a first step, we’ll call a function at the end of our module to decorate everything:

| |

Our magic() function needs to do 2 things:

- Get the module it was called in;

- and decorate all the functions.

| |

To get the calling module, we use inspect.stack to traverse the callstack and find the right module

| |

We get the callstack, take the frame 2 level above us (the caller to magic()), and use inspect.getmodule to get the relevant module.

Then we decorate our functions.

| |

Our function takes a module and modifies it.

To do this, we’re using some of Python’s reflection capabilities.

inspect.getmembers(obj) returns all the member variables of a given object.

In our case - a module.

inspect.isroutine(obj) tells us whether a value is a function.

inspect.getmodule(obj) returns the module an object was defined in.

setattr(obj, name, value) sets an object attribute named name to value.

And with that our magic() function is operational!

For our next trick, we’ll make the call to magic() disappear as well.

This means that we need to somehow make the from cpp import magic line

do the actual magic.

“But Tamir! An import is not a function call!” you might say. Well, let’s see what a Python import actually does.

Import Internals

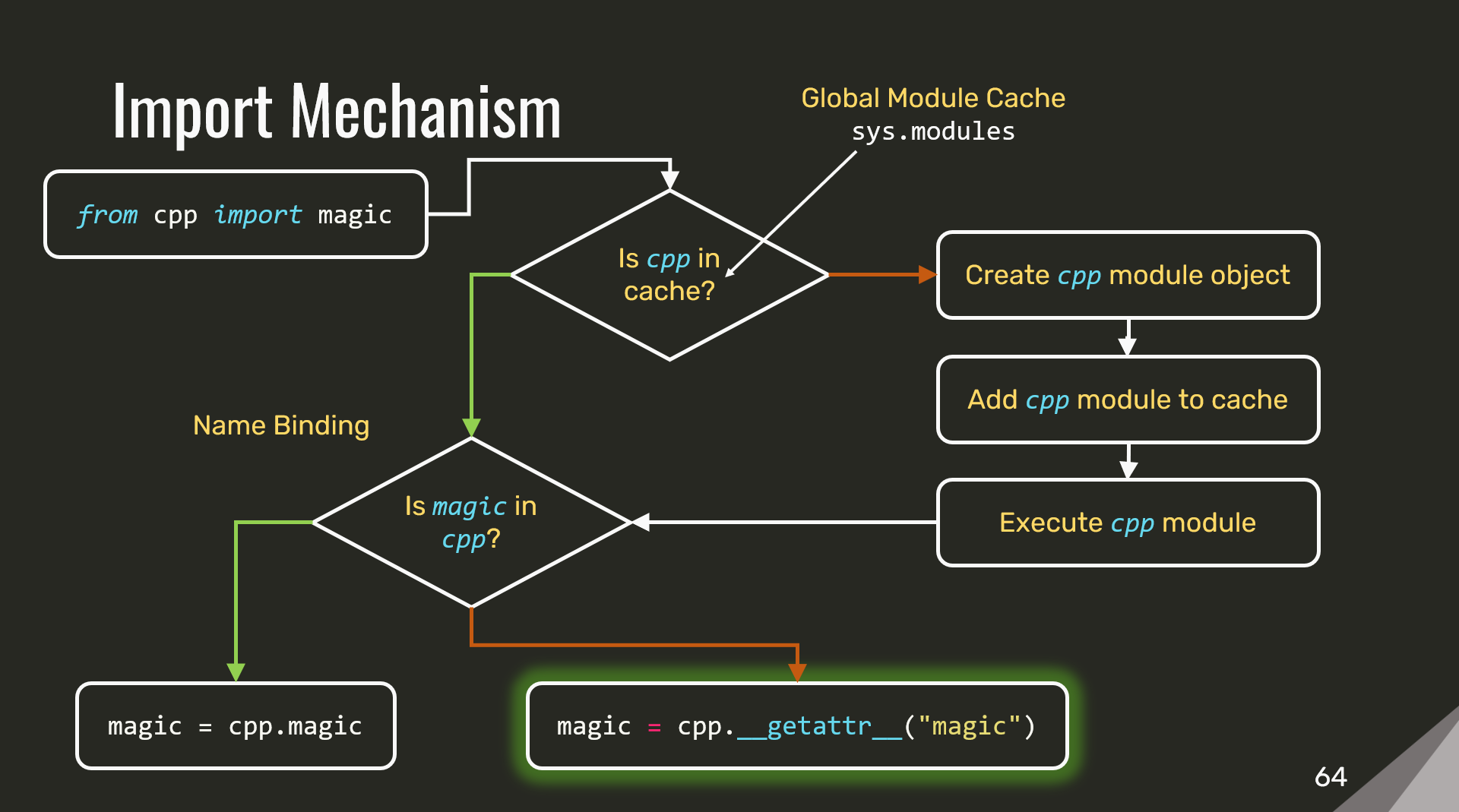

When we run from cpp import magic we go through the following steps.

First, we look for a module named cpp in the global module cache,

sys.modules.

If it is present, the module is already loaded, and we can skip to name binding.

If it is not present in the cache, we find it on disk, create a module object from it, place the module object in the cache, and then execute the module.

Note that we first store it in the cache, and only then execute the module. This is important as Python allows for cyclic imports, and we want to avoid recursion. It will also come in handy later.

Once we finish executing the module, we need to bind the relevant names.

In this case - magic.

Python takes the cpp module from sys.modules and looks for magic

inside it.

If it finds it, it binds that to the name magic.

Lastly, Python modules may define a __getattr__(name) function.

If it is defined, it is called whenever we try to import a name that isn’t present in the module.

| |

So, as you can see - import can be a function call!

| |

This converts the import to a call and allows C++ to work it’s magic.

| |

Well, almost…

You see, since we’re imported on the first line of the module, the module is empty. The functions we want to decorate are not yet defined. To fix this, we can do one of two things.

The first option is to import our magic at the end of the file

| |

This works, but feels far from magical.

The other option, then, is to import the modules ourselves! With the fully imported module at hand, we can modify it as we wish.

Import Cycles

This means that our _magic() function is going to change a little:

| |

Using Python’s import mechanisms, we import another instance of the module that imported us.

We use it’s name and path to import it again, then store it in the global module cache instead of the original.

This is where the fact that the cache is filled prior to module execution comes in handy!

We execute the module, to define all the types, and then decorate the functions.

With this change, we can now write the import at the top again:

| |

And recurse infinitely.

Our module runs the magic() function.

The magic() function imports our module.

The module runs the magic() function.

The magic() function imports our module.

And so on and so forth.

To fix that, we add a flag to all the modules we import, before executing them.

Then, in our magic() function, we check for the flag.

| |

This breaks the recursion, but we still have an issue.

Once we finish all of our import magic, we return to the module that triggered the magic.

This module has not yet been modified.

Once we return to it, it’ll run to completion.

In the case of our main module - main() will run twice.

First, when we import it inside magic().

Second, when we return to the main module and let it execute.

In both cases, we’ll be running the non-decorated version.

This is not at all what we want.

To avoid this sort of thing, Python code usually uses the following:

| |

__name__ always holds the name of the current module.

In the case of the main module, it’ll be "__main__".

This ensures that when a module is imported (and used as a library) it will not run the main() function.

In our case, this will not be enough. First, we actually do import the module. Second, we need to ensure that once we’re done, the original doesn’t run.

So once again, we modify our magic function!

| |

Instead of preventing main() from running, we call it explicitly.

That means that, like in C++ code, we don’t need to call main() explicitly in our code.

| |

When we’re done, we call sys.exit to terminate the process, and never actually reach the module that initially imported us.

Class Boilerplate

Another thing we want to address is the code inside our Greeter.

We are currently writing a lot of boilerplate there.

We have the __enter__ method, the unused __exit__ arguments, and pushing

the instance into the dtor stack.

With a bit of inheritance, we can move all that boilerplate out of Greeter.

| |

That’s great.

Now as we add more classes, we don’t need to handle all that annoying dtor-stack stuff.

As a bonus - our constructor is now named Greeter, as it would be in C++; and our destructor is _Greeter, as ~ is not valid in Python identifiers.

But… We’re still missing something.

We decorated all free functions with cpp_function, but we still need to decorate all of our member functions.

| |

This is similar to what we did with the modules, but this time we check for magic methods, as we don’t wanna decorate them.

Last but not least - we want to make it truly implicit.

Currently, we use inheritance explicitly to extend our Greeter class with the CppClass methods.

In essence, we’re injecting 3 methods into our Greeter class - __init__, __enter__, and __exit__.

We’re using inheritance, but we can use a decorator just as well.

We take the class, make the relevant modifications, then return the modified version.

| |

This might look a bit funky, but it integrates well with our previous work decorating all free functions.

A few extra touches are moving the method decoration out of the __init__ method, so that it only happens once; and adding a __cpp_class__ attribute so that our code can tell it’s actually a C++-style class.

| |

Lastly, we modify _magic to decorate classes as well:

| |

And with that, are classes are automatically converted to C++ classes!

| |

Composable

We’ve come a long way so far, and our destructors are called automatically and implicitly. The next step is making our classes composable. Or, more specifically - handling members properly.

Before we do that, let’s see where we are now:

| |

We have fewer lines, and fewer resource-management lines.

That’s great.

But we also have a new issue - double free!

When we create the ZipFile object, it gets pushed into the dtor-scope of the BetterArchiveReader ctor.

Later, when we get to the dtor and call .close() on it, it is already closed!

To fix that, we need to somehow remove the ZipFile from the function scope, and let the BetterArchiveReader handle it instead.

So something like:

| |

Which would call a .remove method on the current DtorScope:

| |

Which will, unfortunately, fail.

list.remove() checks for equality, not identity.

So if we have multiple object that compare equal - we’re in for some painful debugging.

To remedy this, we’ll borrow a trick from the C++ playbook and use a comparison object:

| |

IdentityComparator wraps the object we provide, replacing the equality check with an identity check, resolving the issue.

And while ZipFile does have a .close method, not all context-managers do.

So we’ll make our code a bit more generic with a call to __exit__:

| |

That’s better, but we’re back to managing the dtors of our objects manually again. Instead, we want assignment to a class member to handle all that automatically.

Descriptors

Unlike C++, Python does not have any form of assignment operators. So we can’t use those. It does, however, have setters and getters. Before we dive into that bit of syntax, let’s look at what we want them to do:

| |

Naturally, we don’t wanna be writing and calling those methods everywhere. To circumvent that, we’ll use “descriptors”, Python’s flavour of getters and setters.

Any class member variable (class, not instance) that implements __set__ and __get__ is a descriptor.

When we later access those variables through an instance, those methods are called to set or get the value from the member.

Adjusting our code to use them, we get:

| |

__set_name__ is another descriptor method.

It is called on class creation (when Python creates the class object, not an instance) to pass the variable name to the descriptor.

Then, the descriptor can derive a unique name from it and use it to store the actual value in the instance.

This takes care of the function-scope.

The next thing to do is make sure when our destructor is called, we call all the member destructors as well.

So in cpp_class, we add a call the member destructors after dealing with the class destructor.

| |

This leaves us with much nicer code:

| |

We just assign a ZipFile to a member, and we’re good to go.

Our member destructors are called automatically.

Annotations

But… That zipfile = CppMember() still bothers me.

It shows some plumbing that is better hidden.

And we can do better.

Python has type annotations. They look something like:

| |

They don’t really do anything, but once we use them, Python stores a mapping between name and SomeType inside our SomeClass object.

And if we have a mapping, we can query it:

| |

And with that, we’ve reached our goal!

We can now write our BestArchiveReader as if it was a C++ class:

| |

Wrapping Up

We started by looking at Python’s take on destructors, and the issues it poses. Then, we took inspiration from C++ and gradually built a “better” solution. We focused on 3 main goals, and achieved them:

- Automatic: destructors are called when / where they are needed.

- Composable: members work automatically, with no added boilerplate.

- Implicit: no extra code; no changes to interfaces; no interface pollution.

But…

Some of you may have noticed a glaring issue. Once a value is created in a function, or assigned to a member variable - we can no longer move it. See, we have ownership, but no move semantics.

There are some extra tricks we can use (and are used in the library) for returning values, but I don’t think the general case is elegantly solvable.

Further Reading

First, thank you for reading this entire post. If you want to play with the concepts I presented here, check the full implementation, you can check it out on my Github. You’ll also find there an implementation of access specifiers, which you’re sure to enjoy.

This was a fun experiment when I first started playing with this, and a fun talk to present. I hope you have fun with this too.